#TOMs100: Interview with Durk Dehner, President and Co-Founder of the Tom of Finland Foundation

In commemoration of the Tom of Finland Centennial on the 8th of March 2020, we publish here an excerpt of an interview conducted with Durk Dehner at the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles in April 2019.

The transcript has been shortened and edited for style, clarity, and content. The full version of the interview files (audio and transcript) are open-access research data stored at the University of Exeter. Researchers can request them by emailing Dr João Florêncio.

João Florêncio: Given my interest in representations of masculinity and how they may have changed, I would like to hear from you. Could you tell me a bit about Tom’s work and its influence in the development of a kind of gay masculinity that is often seen to be hyper-masculine?

Durk Dehner: So my name is Durk Dehner and I’m president and co founder of the Tom of Finland Foundation. I was born in 1949 and I grew up in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, a rocky mountain city that pretty much had a cowboy mentality, that was very much about nature. Discovering that I was homosexual at the early age of five, I was very much looking around me to find some kind of similar identity in individuals, and at the time that I was raised, the only representation that I could find was Liberace. And it was so detestable to me that I kept on looking but I wasn’t finding any sort of overt examples of homosexual men that were positive. I mean, not that Liberace was “unpositive.” I mean, he didn’t present himself as a negative, but I definitely interpreted him as a negative that I didn’t want to become. I didn’t quite understand how my parents could even watch him on TV. Around me, the whole semblance of being a homosexual meant that you were effeminate, and effeminacy was interpreted negatively. So kids that were effeminate were made fun of. So, in many ways, the early years for me were about hiding. Yet, at the same time, I didn’t adopt the whole Christian ethic of the evil of homosexuality… I just didn’t seem to find any kind of role models. As I grew up, I was actually rather semi-open, in that my parents were aware of my homosexuality even though I was a father at 16. I was an explorer, for sure, trying all different kinds of things. I was attracted to tough, black leather-jacketed guys and I would follow them. I was down at the motorcycle shop when I was—you know—nine and ten, asking the guys on Saturday mornings whether I could run and get them a soda, or whether I could polish their bikes in exchange for maybe getting a ride around the block. And so they were, in fact, my archetypes. The first time I got to ride on the back of someone that I just adored, and wanted to actually have him, I realised that I didn’t know whether I wanted to melt into the back of his leather jacket and be inside of him— just become him, like, absorbed into him—or whether I wanted to devour him. I was going between the two, but either way it really was about us becoming one. In many ways, I was growing up and becoming that man whom, in fact, I desired. I desired him and so I became him, I became the guy that I had desired.

JF: What was it about this archetype of men that you think drew you to them?

DD: I grew up in a household where that wasn’t over exaggerated, but my father was a blue-collar worker. I would get dressed up in his work gear, his rubber boots… I would, at the age of five, lay down all of his rubber gear… He worked outside for the power company, so there were rubber boots and rubber raincoats around and I would take all my clothes off and I would roll around on top of this rubber gear. I found it to be so sensuous at the age of five. And there’s no logical reason; it was just something that I was urged to do and I just did accordingly, I sort of just went with the desires. But the role-modelling, for sure, it was motorcycles and leather. I was craving and desired those kind of guys from so young. I would go down to the motorcycle shop and I would go behind where all the used motorcycles were when they were closed, and I would climb over the fence and I would lay around on top of the bikes and smell the grease and oil. There was an early connection to that, to what I was loving and liking in that manhood.

Anyways, I was in pursuit of an identity—my identity—it was already moulding. I mean, I lived in a lower-class neighbourhood. There were definitely—quote—“thug” types of leather-clad guys that had grown around and looked for trouble. In many ways I was becoming them. So at 14, I saw an ad in the magazine called After Dark, for which ironically, I would end up being a model years later. I found it at the public library and it was advertising a leather company that made leather clothes in New York City. So I wrote them, sent them my measurements and they told me how much money to send them. I ordered a pair of black leather pants and then got them. And I wore them… I wore them to high school. There was no rule… you could not wear blue jeans but there was no rule against wearing leather pants. And those pants were so tight on me, they just oozed sex. I took great pleasure in wearing them to school, and the vice-principal just flipping out that he couldn’t prevent me from wearing those pants because there was no law against it, no rule. That was very much indicative of me… being able to play the rules—not violate but really push them.

But it was not until I was 26 that I actually discovered Tom of Finland’s work. I’d been to Europe when I was 18… For a whole year I hitchhiked around Europe and North Africa. I went back and finished high school, then went on to university, moved to Vancouver, lived in the woods with my boyfriend, who was from Uruguay. We then moved to Los Angeles in 1970 and we were here for a year. I was exploding and experiencing all sorts of different things. But when I was in New York, I saw Tom of Finland’s art on a bulletin board in a bar. And it was not even a really good reproduction. It was like a leather jailer—he was holding some keys to a jail cell. And it was the psychological side of all of that… it just inspired me, I was attracted to it. I didn’t really understand why… I mean, it was attractive to my eye, for sure, but why did it have such an emotional impact on me? I was bewildered because I had not had art do that for me before. I had desired stuff, but they had not somehow affected me emotionally. And it so happened that I had just met another artist whose name was Dom or Judas. He had become a new acquaintance of mine as a result of my winning a leather contest at a bar called The Eagle’s Nest. So I met him and asked him who had done that work. He told me and I said it had had that impact on me. Then he said “well, I have his address.” So I wrote Tom a letter acknowledging that experience, and we became pen pals. Then things just evolved. So the whole development of this masculinity, I see that it was part of my birth and there was absolutely nothing that I could find in my youth that reflected being homosexual as any kind of positive identity.

JF: When you were looking at those negatives depictions did you also have a sense that there were parts of them that also related to parts of you?

“When I was in San Francisco, I was at a leather bar in the middle of the week when it was quieter and a drag queen was standing at the bar next to me. She said, ‘Honey, what’s your story?,’ and I said to her ‘Well, I’m here to find my family and to find myself.’ So she just snapped her fingers and said ‘Honey, you can be anything you want to be, here.'”

DD: Yes. The fear is that self-loathing is just below the surface. And that when you’re hiding, when you’re hiding and you don’t want to be called upon being something because you don’t have any sort of positive self-identity—because there’s nothing around you to validate that—you feel like you’re an imposter. You feel like you’re really a fake and that the best thing you can do is to get by without becoming noticed, so that you don’t get called upon it. Because when I look back on pictures of myself during that whole early development period I see a kid that was so shy. In school, I was so shy… I was so shy that I wouldn’t answer questions. I was just painfully shy. And yet, around that same age— at the age of nine—I was going to public bathrooms and watching men have sex. Even though I wouldn’t engage with them, I was watching how they did it and what they did. So there you have an individual who was looking for validation. And yet, I look back, I look at pictures, and I go, “how could this little kid have done this? How could he?” Because I look at pictures of myself at 9 and 11 and I looked so young… But then, you know, at the same time here’s a kid who had a baby at 16, you know? And I stayed with my girlfriend for a year. And really, my parents were really pretty amazing back in the day—they didn’t judge. They didn’t judge in that when things would go down they would say “well, you’re going to have to be responsible for this, so pull it together because you’re going to have to take care of it.” And that really aided me in learning how to live life. And so, later, when I started to go to places like Vancouver, and Seattle and San Francisco, I was looking for a family. You have this 19-year-old who had already traveled extensively and had had sex, but the people who taught me how to cruise were drag queens in Vancouver because I didn’t quite get the part of how you can look afar and make eye contact, and then do gestures and show the relationship. And so it was them who actually taught me. And not too long after that, when I was in San Francisco, I was at a leather bar in the middle of the week when it was quieter and a drag queen was standing at the bar next to me. She said, “Honey, what’s your story?,” and I said to her “Well, I’m here to find my family and to find myself.” So she just snapped her fingers and said “Honey, you can be anything you want to be, here.” And that really penetrated me. It penetrated me and it was she who gave me permission, who told me that I could really just create myself and really select whatever I wanted to be. So I discovered that I was part of a community that was so free. And that you could add to it, you didn’t have to just select what was on that table, you could really do anything. So anyways, coming across Tom’s work was just this affirmation of it. The masculinity was so deep, I really realised that I was part of something that was burgeoning, that it was part of the transition from the hippie movement and the beginning of the Gay Liberation Front. Discovering Tom’s work and then learning about his history, and how the whole masculine leather culture had been evolving in the Western world during the war, in America and Europe.

I think that people misinterpret what Tom gave us, and he did this right after he came out of the war, having killed people, and having stabbed one particular soldier from Russia in the back with a knife because he couldn’t let him shoot him. And when he turned the body to ID it, he realised he was the most handsome, most beautiful specimen of God’s creation, and he just cried and broke down and wept on this guy’s chest. And, and he swore to himself that he would never kill another man. And he came out of the war with a decision to do something to sort of make it right and to see if he could change the way society looked upon homosexuals. He tried different things, he tried going to the bars, where there were effeminate men very sort of… very Quentin Crisp. And he really, he really tried to see if he could fit in there. But he said to me that it just didn’t work. He didn’t feel like he was being himself, he was being artificial.

Speaking about artificial, we tend to think that sometimes the masculinity that we actually take on is artificial, that it’s not real. And how can we be real? I mean, are we, are we actually really men? Or are we some kind of weird hybrid between men and women, and all of that fucked-up shit, right? The thing that I learned, my wisdom over the years, it’s that it doesn’t matter what you are. The thing is, we do that all the time. We do it from watching our parents, our mothers, our fathers our siblings, our heroes in the films. And then what happens is that, when you’re not happy, they say “if you want to be happy, you got to act happy;” you got to sort of play it a bit. And then what happens is that it becomes you.

And so the whole leather culture—in straight culture and in gay culture, and in the early years—it was mixed. They were together and then they eventually separated. So the gay guys that were part of the leather culture eventually sort of branched off and created their own sort of gangs and clubs. In Europe, Tom was drawing guys wearing leather jodhpurs—like the motorcycle riding pants worn during the war. And once he saw Marlon Brando in The Wild One and he saw the black leather jacket and how sexy it was. Even though there was black leather in the war with the Nazis—some of it— where it really rang home for Tom was when he saw the motorcycle jacket. And so he just immediately…you can see it in his work: over the space of a year it just transposed into black leather. And then what happened was that his friends in England would send him pictures of what was happening there with the leather culture and he would draw those and then expand upon them. If there was one buckle on the boot, he’d put two and then send drawings back and they would get ideas and they’d go to a leather tailor.

You know, the thing is that one of the stories that I love about Tom, and about how unabashed he was, is that he wanted to get close to the guys who were riding the motorcycle circuit at the racetracks. And he didn’t own a motorcycle, he didn’t know how to ride a motorcycle. But he thought “I’m going to get a leather motorcycle racing suit made.” And he went and had one made for himself. And then, like a rooster, he went into the inner circle of the race tracks and was hanging out with all the other racers, right? Was he an imposter? Yes. Did he care? No. Was he just totally absorbing it all? Yes. And he didn’t suffer from insecurity… He grew up with a sense of self. His parents must have done a really good job with him, you know, because he had so much self confidence and willingness to try things, you know? I mean, he would go up to people in the streets, guys that he could smell were homo, and show them some of the drawings he’d done to see what their reaction was, you know? And it wasn’t always favourable. So, what was happening then was that all of that was evolving and it was happening internationally. And you could see it happening in Western Europe, in the United States, in Australia, in South Africa. It was all blossoming in all those different places. You may have thought “well, it’s a Nordic thing” but it went far beyond that.

JF: So Tom’s work had a role to play in that?

DD: Absolutely! Because the thing is that, just so you know: when his stamp came out four years ago in Finland, they announced it before they actually released it. And so the Finnish post office was so surprised that they got pre-orders from 158 different countries in the world. How many countries are there in the world? To some degree, what I experienced in his work, what pulled me towards it that day in New York City, must have transpired with other people because they started passing it around; it was its own phenomenon. And, if I can speak for him, he gave up using words, he decided to use just his ability to embed into a drawing a message of feeling—a nuance. He was successful in creating that international phenomenon before there was the internet.

JF: One of the things I find particularly interesting in a lot of his drawings, especially when there’s more than just two guys, is that, on the one hand, there is this sense of toughness, of really tough guys, but then there’s always equally a sense of vulnerability and kindness. For instance, in the ways in which they look at one another. And to me, interested as I am in studying masculinities, it is really interesting to see someone who was so fundamental to the development of the visual standard of a certain kind of gay hyper-masculinity already presenting all those layers in his figures.

“he was providing those archetypes, those images that young developing homosexuals could grab on to, would hold on to. And it was theirs—they knew it was theirs—it was not a straight guy that they were trying to become, it was homo, and it was male.”

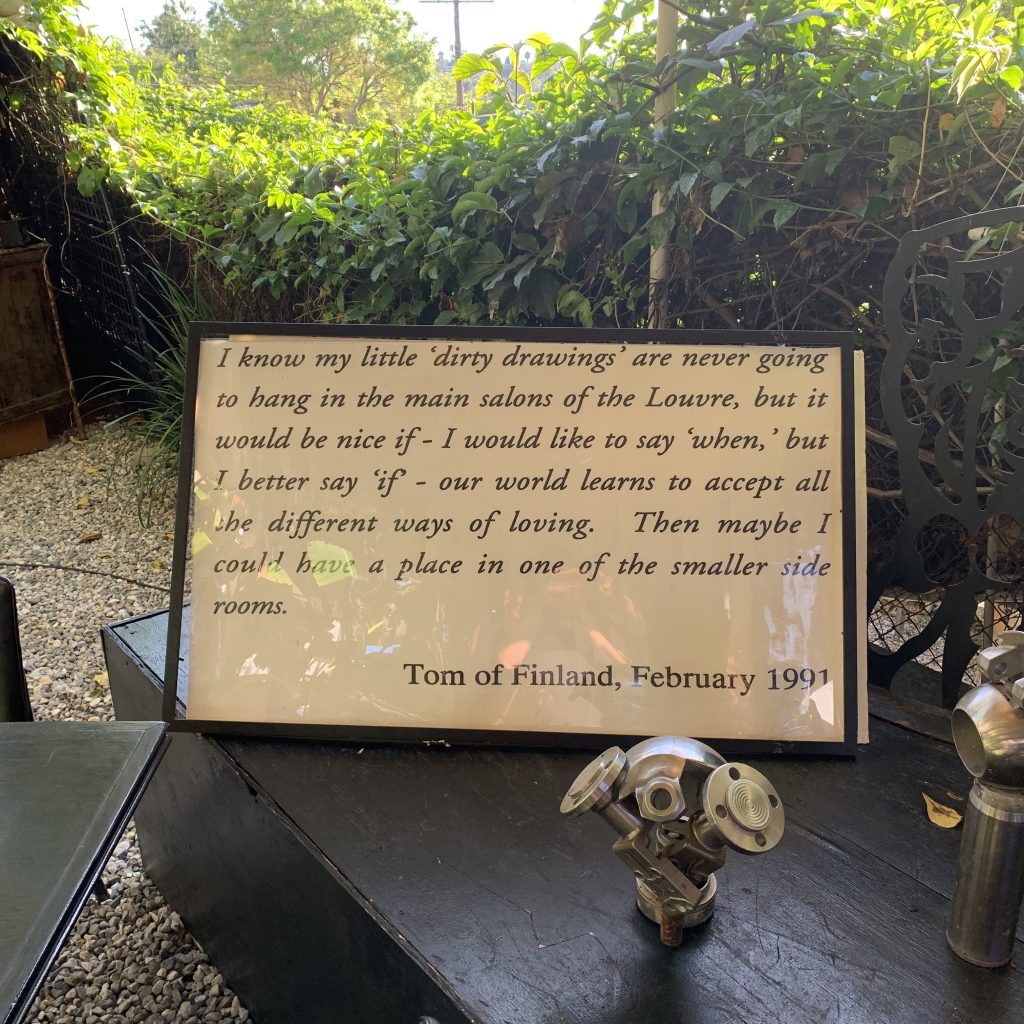

DD: They are the way we are. I mean, that’s the thing about it. I’ll tell you something that has happened: Soon after Tom passed away—he died in 91—what came out in 92 and 93 was Queer Nation. Queer nation was all about the radicalisation of our movement. And they were young—they were, like, in their late teens, early 20s. And they didn’t really know much about our history. And we would get very accosting phone calls from them complaining to us about how Tom was such a rip-off, that his work was just glamorising the heterosexual role model. But if they had let us talk, we would have told them that “no, you don’t understand, you don’t know… you don’t know your history.” And the history was, first of all, that he provided some masculine archetypes that were not available to us, that we did not have, that had not been given to us by our fathers, or that—you know—that we had been denied. He felt that to be so unfair…. And the reason why he used to say “these damn queens!” was because the way they were depicted was really negative. There wasn’t a lot of fun in the way that effeminate men were depicted. And so it was about taking charge of it. And so what he did was that he took charge. So I thought he was like, the perfect subversive, because of what he did… he just slowly took it up until it became such a phenomenon. And no, he wasn’t the only source of it. But he was providing those archetypes, those images that young developing homosexuals could grab on to, would hold on to. And it was theirs—they knew it was theirs—it was not a straight guy that they were trying to become, it was homo, and it was male. And it was like, “okay, I can grow into this, I can become this.” And I must say that when I first started representing him and creating events—wow—what an education that was for me! Because I was somebody who had not grown up with that work, who didn’t know anything about him till I was 26. And you had to hear those young guys come and stand in line for hours to meet him and to just thank him… Like, they didn’t mind waiting, they didn’t get grumpy, they just wanted the opportunity to thank him for what he had given them, you know? So that was an education for me. And then if you really look at it, you see the layers of how sensitive they are, how vulnerable they are, and how much fun they’re having, you know? I mean, yes, he did lots of things in the night time, but he did many more drawings about being out in the daylight, and how important the sun was… about reflecting, about pride, and how the smiles were really about being proud of who they were and, an… and nature, water and sunshine and forests, and how symbolic—very Finnish—but also very universal.

And, you know, it was extremely painful when we were having such an amazing time and AIDS came. And he was just so heavy, thinking that his participation had actually been part of the—not the cause, because he didn’t cause AIDS—but that he had encouraged us to be vulnerable and to be free. And then that horrible disease came upon us and took so many of us. And he, and us, and me…I mean, we came about with the best strategy we could, and that was to try to save as many asses as we could. And we did that through just trying to promote safer sex until there was some other solution, you know? It was not easy for him but he rose, you know? He rose to that occasion and did drawings that reflected that. And we did PR campaigns and things like that. So anyways, when Act Up would call, I would say—if I was the one who answered—I‘d say “you know what? If he was alive today, he would draw you with a skirt on and he would want you to just follow your path. And, and if you want to be liberated by wearing a skirt, he would he would absolutely promote and condone that.” Because what he was about was freedom for us, you know? He was like… he was the one. And not that he was alone in that, you know? There was a kind of camaraderie among artists in that they were not in competition with each other. They loved each other’s work, they celebrated it, and they encouraged it. And so that whole time period was really empowering, in that we were all about empowering each other. And the whole advent of the leather contest and that sort of display of masculinity, it was it was really about just, you know… We see straights had their contests, whatever they were, you know? So this was an opportunity for us to put our own up on the pedestal, and to admire it, to goggle at it, to appreciate it. But it didn’t stay static, it changed with the times: when it was time to actually be political, to be a radical, to actually save other people’s lives, to see if we could change the medical system and the government. Yeah, it was sort of tough because you had to give up the all the partying and put more focus into actually doing some of the civil civil rights part of it.

JF: When I was researching in your library, I came across an issue of [US gay fetish magazine Drummer that had a really poignant letter to the editor. It had been written in response to Geoff Mains’s essay “The View from the Sling,” which had been published in the magazine a couple of issues earlier. What really touched me about the letter was that it had been sent not by their typical male reader but by a woman who wrote about how much fun she used to have with Geoff and all her other gay “brothers” at the [sex club] Catacombs in San Francisco, and how they had welcomed her into such free sexual environment. I found that interesting because we don’t normally think about gay leather culture being that open, neither presently nor that early on. And that has reminded me about all the work you’ve done with the Tom of Finland Foundation to open it up to all kinds of folk.

DD: Yes, Geoff was very wise. And he actually caught on to it early, that we are tribal. So many of our characteristics, our actions and customs, are really tribal customs. I really felt at an early age that I was part of creating those tribal customs. And yet, it was hard for me to open myself up to allowing trans people into into the community, into the leather community, because I felt like I had to protect it. I had to protect it, because I felt like it was so fragile. And, in fact, it is very fragile… I think people don’t realise that. So I looked at it, and I said, “okay, well, I’m old—older anyways—and if I get to be excluded because of it being something that I’m too old in order to fit in, then so be it, if it means that the tribe will live on by that exclusion. You’re talking to somebody who produced a lot of warehouse parties and dance parties, you know, with 100 to 5000 people, you know? And I had to work with dynamics, and I had to see what it would take to make those parties a success. And it wasn’t about me or about age; it was about attitude and it was about friendliness. And Tom taught me a lot. I really modelled a lot of my parties after what he emulated in his drawings, because it was the answer. If you could get people to be friendly, easy and relax, then the part of them that was natural would come out. And that would actually produce the right energy for the party to be a success, because then everyone would be interacting with each other, right? So I have supported and nurtured an environment here [at the Tom of Finland Foundation] where everyone is welcome. And whatever they identify as, that’s fine, and they can contribute and be a full-fledged participant here. Somewhere in myself, I still hold this fantasy about living in a communal environment that is fully male. And now, pretty soon, I probably won’t be able to define what that means anymore. Because, you know, I mean, I’m being affected by just the definition of what is sexy, what is a gender? Because I’m surrounded by younger people who are gender fluid. And would I ever want to take that away from them? No. But I still really love it when I’m in a completely masculine environment. And what is masculine? Well, my masculinity certainly has the ability to flip my hands up and to call someone else “girl,” you know? So that’s sort of my definition, and because there’s always room for that. Otherwise you take yourself too seriously.

JF: You’ve been talking about where we were and where we are today. You talked about how people were using sex to come together, to find their families through sex but then the tragedy of AIDS came and changed everything. Today, we seem to be living in this moment where AIDS—to some of us at least, to those of us living in the right place, with the right skin colour and financial circumstances—is no longer something we fear, something that we need to worry about. Do you think there may be an opportunity here for us to pick up where we left?

“in some ways, I really feel that we’re the gift. I feel that we’re extremely special as beings. And if you want to ask me who “we” is, well you know: if you feel part of the ‘we,’ then you’re part of the ‘we.'”

DD: Yes. I’m glad you brought this up because I ask myself, “what is my purpose? Now, at this age—I’m going to be 70 this year—what is my purpose? What is my mission?” And my mission is to empower. To empower as many young people as I can. And, actually, to encourage them to go off, to go out of this, out of the cities, to go out into the country, and to find… and to live communally. I really feel that if we actually separate ourselves from what’s going on here in the cities, and go in groups live in the country, that we will naturally discover what it is, where to go, and how to evolve. That’s my vision. I mean, the vision that I had was that there would be this huge amount of country land, both in Europe and in North America, and everyone would own an acre and they could build whatever they wanted on that acreage. And that it would be—like—huge. It would be like 1000 acres, right? And it would all be connected. And, obviously, closer inside the centre of it, it would be where there would be much more mega happening. And where that would all start to express itself would in the freedom, because I don’t feel like we’re very free anymore. Tthe thing that I was tapping into as a young man, it was how exciting it was that we were creating it, we were actually in the present moment and we were creating our culture as we actually wanted to see it take place. And so sexuality was such a big part of it. I mean, I met life partners and people with whom I had relationships that went on for eight years, you know? We met at a sex club and the next thing we knew we were cohabiting… Anyways, this house, the Tom House, is a product of that. It was me and it was my lover, and my ex lover and his lover. The four of us were living somewhere else, in a house, and we agreed that we would see if we could find a house to buy. Then they all died. But they didn’t… they didn’t die in vain. They were part of the experiment, you know? The experiment of being able to share, you know? Of sharing what we had and… and being part of helping each other grow. And… and free love, you know? It was definitely part of it… what the love generation also brought to the table. And so the experimentation of having different structures of love, relationships. And that has to continue on. Within the kink community, I think there are so many things that are not really well done, well done in the sense that they’re not well explored. And what I mean by that is that there’s a lot of masters and tops that are not well versed. They’ve not given the knowledge and the technique to really manifest themselves fully. They may be able to reap it from here and there, just by osmosis. But it would be really good if they were really given the ability and the nurturing to be empowered. So that they could really see how they can really become something that is so full of energy and then direct and guide a bottom, a slave. I mean, it’s interesting that I’ve done a lot of meditation and transcendental type of stuff over my lifetime. And the idea of having a teacher, a guru, that would actually tell you, “okay, do this.” You don’t get to ask them why; you just do it. And as a result of doing it, there’s lessons that transpire out of that, because it’s no accident that there’s so many bottoms and slaves that really want to surrender. Because surrendering is part of a transcendental experience and we’re conscious beings… we are more conscious in general than our heterosexual counterparts. And so, of course, we want to explore what it is to actually give up control and see what it is, what it does feel like. And it’s about trust. And the thing that was really amazing was that—when I got into that state of mind—that I was all-knowing, that I really had this experience, and that I trusted in what came through me, what was coming through me. And the thing is that I was so perceptive of what was needed and wanted by those who were willing to receive it through me. But that’s a very delicate thing… If only I could just empower younger guys to actually trust themselves. So if I can empower whoever reads this that you’re doing, if nothing else, take away the ability to just trust in yourself and empower yourself to go forth. And trust in it because it will, in fact, reveal it… it will show it, you know? I feel like the only way is through that. And so, if we follow that way, then it will unfold, you know? Because, in some ways, I really feel that we’re the gift. I feel that we’re extremely special as beings. And if you want to ask me who “we” is, well you know: if you feel part of the “we,” then you’re part of the “we.”